In the West Bank, only a few crops thrive that have adapted to the extreme dry conditions in summer. But for the farmers west of the city of Nablus, a new source of water has now been found that will reduce their dependency on rain.

Video: How the sewage treatment plant in Nablus creates perspectives (KfW Group/Christian Chua, Thomas Schuch, Stephan Sperl).

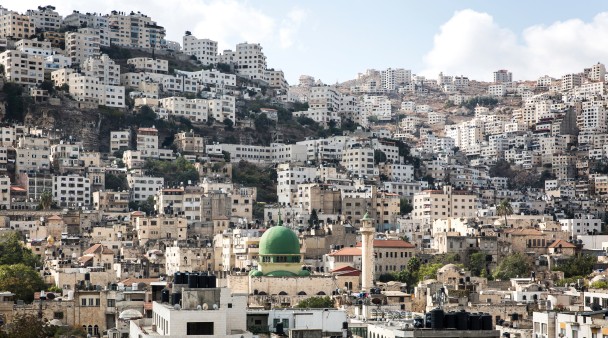

The Palestinian farmer laughs. “Where has the water come from until now?” he repeats the question. “We haven’t had any water until now!” is his answer. And he doesn’t laugh because he thinks it’s funny. Khaled Mkheimer’s field (picture above) is located in the Palestinian Autonomous Area near the city of Nablus. He has no choice but to wait every year for the rain, which usually starts in November. This means that he has to grow plants that don’t need much water.

The domestic olive variety is one of these plants. It is extremely robust and copes well with the hot sun and the dry soils of the West Bank in summer. “The yields are okay, but could be better, of course,” says Sana, Khaled’s wife, who farms the field together with her husband, and adds: “How wonderful it would be if we didn’t have to rely solely on the scarce rainfall.”

She heard from Mohamad Atari, a farmer friend of hers, that her wish could come true. Mohamad also grows olive trees, almonds and a few citrus bushes. Sana recounts how enthusiastic Mohamad had spoken about the possibility of generating an additional yield of 40 euros – per tree, per year. Their land can be used more effectively through irrigation with treated water from a nearby sewage treatment plant.

Khaled and Sana Mkheimer asked Yazan Odeh to explain exactly how this works. Yazan is the head engineer at the West Nablus sewage treatment plant. He and his team gave farmers from the neighbourhood information about their water concept in conversations, meetings and regular workshops. And they needed some convincing. Of course the drought-stricken farmers thought it was good to have water, useful as well, but did it have to come from the sewage plant?

Read more under the image gallery.

Around 200,000 people in the city of Nablus and the surrounding area benefit from the sewage plant.

As drinking water

Wastewater can also be treated with suitable technical processes for use as drinking water. KfW provided support for one of the few existing plants in Windhoek/Namibia, the Goreangab water reclamation plant.

Learn moreFirst experiments with treated wastewater

“In Palestine,” says Yazan, “using treated wastewater in agriculture is a new idea.” In order to convince them and to show the farmers that it works, the engineers created fields on the premises of the sewage treatment plant. They launched their own test series. They wanted to figure out what grows and thrives particularly well with the treated water. They planted olives, grasses, avocados – successfully. Other crops didn’t survive the trial period. The experiments made sense, if only because no one in this dry region had experience with continuously available water.

After the initial successes, the next step followed: approaching farmers in the immediate vicinity to provide them with treated water – in the test phase even free of charge. One of them was Mohamad Atari, who only needed a relatively short pipe to his field to let the water from the sewage plant flow to his trees.

“In Palestine using treated wastewater in agriculture is a new idea.”

Mohamad has been working as an olive grower for a long time – “since birth,” as he says. When he talks about the water from the sewage plant, he practically starts to rave. “This water allows me to grow plants that produce very good yields in terms of quality, quantity and profitability,” he emphasises, citing a few examples: “What normally takes a tree five or six years to grow, can be achieved in just two or three years with treated wastewater. He points to a four-year-old olive tree: “A tree like this used to yield 2 litres of oil before regular irrigation, and only if it bore fruit, which unfortunately was not the case every year. It now produces six litres annually.”

He uses an almond tree to explain his financial advantage: “With irrigation, I generate 50 euros with this tree. With only rain, I would only generate ten euros.” This is because the water has so many nutrients. Mohamad is convinced that this has also made his plants less susceptible to pests. He only needs to use pesticides twice a year on the irrigated fields. Faster growing trees with higher yields in shorter cycles: something that would make any management consultant happy and Mohamad Atari is pleased, too.

In agriculture

There is a shortage of water for agriculture in many countries of the world. One solution is to supply wastewater that has been treated for reuse. KfW is therefore already supporting several projects around the world, not only in Nablus but also in Jordan, for example, where farmers can irrigate their fields with treated water from three wastewater treatment plants (Central Irbid, Wadi Arab, Shallalah).

Workshops for farmers from Nablus

Together with the Mkheimer family and other farmers from the neighbouring fields, he visited the experimental fields on the grounds of the sewage treatment plant. In weekly courses offered there by the Ministry of Agriculture, they learned about the advantages and disadvantages of different plants. Experts updated them on state-of-the-art of farming techniques and gave them the opportunity to try out what they had learned. As can be expected, the farmers are now impatient for the next project step to start, which will supply the water to their plots.

The planning and preparations have largely been completed, so that the next step can start this year. As with the entire plant, the irrigation project is also being financed by the Federal Ministry for Economic Cooperation and Development (BMZ) via KfW with ten million euros. Jonas Blume, Director of KfW’s office in the Palestinian Territories, calls the project a “showcase project” because: “It is about strengthening agriculture, i.e. an economic development project where jobs are created and income is generated. The goal continues to be to protect the environment. This is accomplished by the sewage treatment plant, as wastewater no longer flows into the landscape, but is treated and used for practical purposes.” After all, it is also a “peace-building project,” emphasises Blume. Due to the water shortage in the Middle East, water distribution is one of the major points of contention between Israelis and Palestinians. This would protect groundwater resources that are shared by everyone – one less conflict.

Khaled and Sana Mkheimer are already considered the most successful farmers in the surrounding area. Nevertheless, they are very much looking forward to the water pipe: “When the water comes, there won’t be any more problems at all,” says Khalid Mkheimer and winks. He knows he’s exaggerating a bit. But this kind of confidence in an otherwise crisis-ridden region shows how far-reaching the impact of the irrigation project is.

Published on KfW Stories: 16 March 2020.

The described project contributes to the following United Nationsʼ Sustainable Development Goals

Goal 2: Zero hunger

Today, 795 million people still go hungry, and two billion people are malnourished. Hunger is not only the most significant health risk, it is also one of the greatest barriers to development. It contributes to flight and displacement and fosters hopelessness and violence. Today, the world produces enough food to ensure sufficient nutrition for everyone. However, due to insufficient infrastructure, trade barriers and armed conflicts, not all people have equal access to food.

All United Nations member states adopted the 2030 Agenda in 2015. At its heart is a list of 17 goals for sustainable development, known as the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs). Our world should become a place where people are able to live in peace with each other in ways that are ecologically compatible, socially just, and economically effective.

Data protection principles

If you click on one of the following icons, your data will be sent to the corresponding social network.

Privacy information