Sahaja Organics helps Indian farmers switch from conventional to organic farming and markets their organic products. Today, 750 organic farmers are members of the marketing network, and an increasing number of farmers are learning about the successful model. But the cooperative had a rocky start.

The managing director

Anitha Reddy runs the NGO Sahaja Samrudha, which promotes organic agriculture around Bangalore.

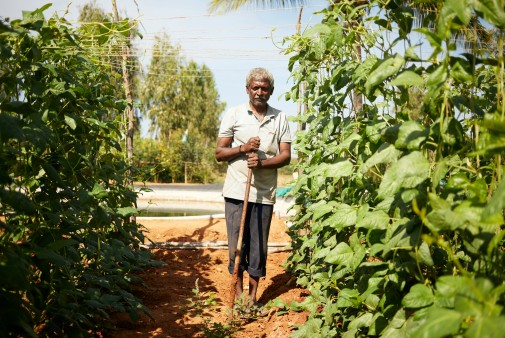

Farmer C. Prakash has 6,000 square metres of cropland, which is just over half a hectare. He farms the land together with his wife. They used to only grow chillies. When they switched to organic farming eight years ago, they also said goodbye to monoculture. Now lentils and pumpkins, okra and beans, spinach and coriander, dill – and yes, even chillies – grow alternately in rows and columns in the Prakash's small field.

The 53-year-old farmer appears satisfied. Since he introduced drip irrigation three years ago – he has his own spring on his land – “I save 50 per cent water”. Prakash not only protects water as a resource and produces herbs and vegetables without chemicals, his family also benefits financially from the decision to go organic. His field generates about 250 euros a month, about a third more than in the days of conventional farming.

“In the beginning it was difficult to persuade farmers of the benefits of organic farming,” says Anitha Reddy about the start of the Sahaja Organics cooperative. She is standing at the cooperative's collection point in the village of Kodalipura, near the Indian high-tech metropolis of Bangalore. 40 organic farmers within a radius of seven kilometres deliver fruit and vegetables here, producers like Prakash, whose field is just a few minutes' walk from the collection point.

The organic farmer

C. Prakash changed his agricultural production over from monoculture to organic production.

Reddy, 50, is a freelance journalist who writes about agricultural issues. She is the Director at Sahaja Samrudha and Trustee at Sahaja Organics, which is dedicated to promoting organic farming and preserving traditional vegetables and grains. She also established the marketing association Sahaja Organics, which now comprises 750 organic farmers around Bangalore, the capital of the state of Karnataka. It is a stronghold of organic agriculture in India.

So the beginning was difficult. Sahaja Organics, founded in 2010, posted losses for several years. “We could not have expanded without a loan,” says B. Somesh, Managing Director of the cooperative. The loan came from KfW via the Indian Agricultural Bank (NABARD), which supported the Bangalore-based association of organic farmers with a total of 38,000 euros.

This is one of 325 umbrella projects in 21 Indian states initiated by NABARD with the support of KfW and the Gesellschaft für Internationale Zusammenarbeit (GIZ) . KfW has invested more than 70 million euros in the programme so far on behalf of the Federal Ministry for Economic Cooperation and Development. The umbrella programme aims to “contribute to protecting the environment through environmentally friendly farming”, says Carolin Gassner, head of South Asia at KfW, “but also to increase the incomes of poor smallholders”.

Read more under the image gallery.

Support for Indian farmers

Around 750 organic farmers belong to the Sahaja Organics marketing network. An increasing number of farmers are learning about the successful model.

The seed bank

In the collection point of the Sahaja Organics cooperatives seeds of old types of vegetable are stored.

In fact, Sahaja Organics farmers earn between 30 and 40 per cent more than they would if they farmed using conventional methods. They do not have to buy herbicides or make their own fertiliser and can bring their products to the collection points instead of having to sell them on the market themselves. This saves a lot of time.

Organic products cost more than conventionally farmed ones. The prices are about 30 per cent higher than for conventional fruits and vegetables. The market for organic food is nevertheless growing. One percent of the food sold in India is said to come from organic production now. The customers are members of the growing middle class.

Reddy directs attention to another special feature of Sahaja Organics. Agriculture, she says, is still a male domain in India. But women also work at the cooperative's collection point in Kodalipura. They weigh the delivered fruits and vegetables, keep records of the products and look after the seed bank with the old varieties.

The founder

N. R. Shetty, former engineer, now self-sufficient, has co-founded the cooperative.

In a warehouse in Bangalore, eggplants, onions, pomegranates, pineapples, bags of rice, lentils and cashew nuts are stored on pallets, along with the chia seeds, amaranth or quinoa grains which are advertised as superfoods. From the Sahaja Organics distribution centre, organic food is transported as far away as 600 kilometres to organic shops in the large cities of Kochi (Kerala State), Hyderabad (Telangana) and Chennai (Tamil Nadu). According to Sahaja Organics Managing Director Somesh, grains account for 55 per cent of products sold, 45 per cent are vegetables. Sahaja Organics has now closed its own shop in Bangalore; the cooperative is now only a wholesaler and in the process of establishing Sahaja Organics as a trademark.

N. R. Shetty is a wiry old man. He is one of the co-founders of Sahaja Samrudha, the organisation where everything started. Shetty, 76, used to work as an engineer at the state-owned telephone company and still farms some land with his wife for their own consumption. Sahaja Organics has been turning a profit for four years now. Farmers from other states inform themselves about the successful agricultural cooperative from Bangalore, but companies are also interested in the concept. “We are proud to be a model,” says Shetty.

Published on KfW Stories: Tuesday, 12 March 2019

The described project contributes to the following United Nationsʼ Sustainable Development Goals

Goal 1: End poverty in all its forms everywhere

Around eleven per cent of the worldʼs population lives in extreme poverty. In 2015 that figure was around 836 million people. They had to live on less than USD 1.25 a day. The global community has set out to end extreme poverty completely by 2030.

All United Nations member states adopted the 2030 Agenda in 2015. At its heart is a list of 17 goals for sustainable development, known as the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs). Our world should become a place where people are able to live in peace with each other in ways that are ecologically compatible, socially just, and economically effective.

Data protection principles

If you click on one of the following icons, your data will be sent to the corresponding social network.

Privacy information