For thousands of farmers around Bangalore, the capital of the Indian state of Karnataka, the alternative to incinerating plant waste and thereby polluting the environment, is to sell the waste with a profit. The German company Bio-Lutions pays for plant remnants which they use as raw material to produce tableware and packaging material. DEG supports the start-up.

Pure recycling

The robust plates and packaging products from Bio-Lutions are cooked up from a plant-and-water mixture without any chemical additives.

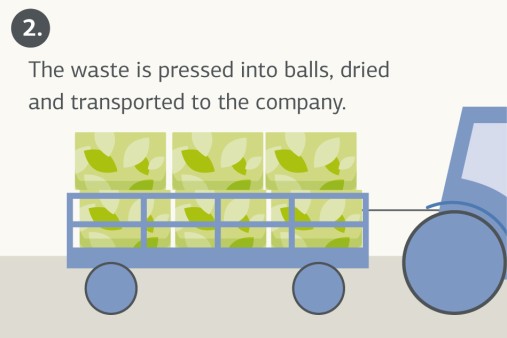

Kurian Mathew stands in the brand new production hall by a main road in Bangalore and says: “It feels good to be able to tell your daughter what her father does: it’s ecological and it earns you money.” Mathew, 43, is head of the Indian production site of the Hamburg company Bio-Lutions. He reaches into a white sack, pulls out a handful of brown fibres and lets them trickle through his fingers. The raw material comes from the collection centre about 15 kilometres from the factory. This is where the delivered crop waste is cleaned, chopped, dried and packed into sacks. There is no shortage of supply since the area around the high-tech city of Bangalore is agricultural land.

Once the Bio-Lutions pilot plant, which started operating in 2017, had proved viable, DEG (a subsidiary of KfW) provided a loan of 500,000 euros to enable the German start-up to commence serial production of tableware and packaging made from renewable raw materials. The funds come from the Up-scaling programme that DEG uses to support innovative medium-sized enterprises in Germany and across the world. With the investment in Bangalore “plastic waste is being reduced and poor farmers are being helped to earn extra income”, says Alexander Feltes, Analyst and Customer Relationshop Manager of DEG.

Pilot plant in India

Years of developing and testing are over: Bio-Lutions went into serial production with packaging and cutlery made from plant waste.

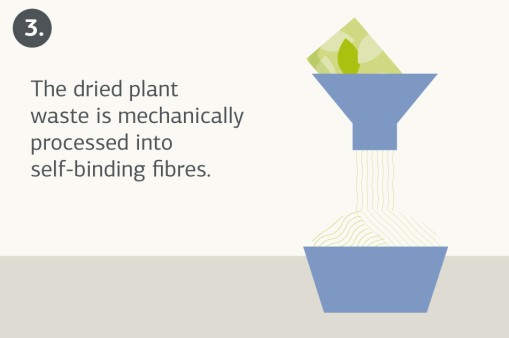

“Everyone thinks it’s such a simple technology, why didn't someone come up with it before?” says Mathew. But Eduardo Gordillo, founder of Bio-Lutions, and the Brandenburg company Zelfo Technology spent several years working on the process to get it right. Their challenge was to develop a sustainable raw material which doesn’t need any chemical additives, is suitable for large-scale production and can compete with cardboard and paper on price.

Neither Mathew nor the Colombian-born Gordillo, who moved to Germany years ago, come from the recycling industry. They are both architects and product designers. They first got to know each other in China a few years ago. The documentary film “Plastic Planet” gave him his ecological and business idea, says Gordillo, 52, who wants to do nothing less than “fundamentally change the world of packaging”.

Mathew is standing before a basin in a clean hall surrounded by the noise of presses working continuously. Once the plant fibres have been split, heated and blended into a sticky pulp, this falls into the large, water-filled vat. A mechanical rake passes through the pulp, which has a very high water content. From here it passes through a pipe into presses, such as those used in paper production.

Read more under the infographic.

Manufacturing process of Bio-Lutions packaging

Step 1

The idea behind the biodegradable packaging is a natural cycle: The agricultural waste is turned into fibres, which in turn can be processed into packaging. After use, the packaging can be composted as organic waste or incinerated with virtually no CO₂ impact.

Get the oceans clean!

In mid-October 2018, KfW Group launched the Clean Oceans Initiative together with the European Investment Bank (EIB) and the French Agence Française de Developpement (AFD). The partners have committed an initial amount of EUR 2 billion for reducing plastic pollution of the oceans.

Learn moreBrown plates and bowls are produced under high pressure. One worker takes them out of the moulds and another trims them. These processes could also be fully automated, but this approach creates jobs. The company currently employs 20 people at the Bangalore site. BIO-LUTIONS currently processes around four tons of plant residues per day. However, the number of presses is to be increased from eight to twelve in the current year. One of Bio-Lutions’ existing customers is the supermarket chain Big Basket, which sells fruit and vegetables in 100 percent degradable cardboard packaging. Hospitals order dishes for medical instruments from Bio-Lutions. The products can also be coated to make them waterproof, oil or grease-resistant.

Supply from the region

In a collection centre close to the factory, the delivered crop waste is cleaned, chopped, dried and packed into sacks.

The business is still confined to India, but Mathew is now reporting “lots of enquiries from Europe”. They are thinking about expanding at the product level as well and are considering producing recyclable, disposable cutlery, which would open up a whole new sales market to the company. For the cutlery production, injection machines would be needed to mould the runny fibrous pulp.

Even waste processing generates some waste. Once a month Bio-Lutions needs to dispose of the water that is repeatedly cleaned and flows back into fibre processing. Mathew leaves the manufacturing hall and leads us through a garden outside the front of the hall. There are no flowers growing here, just crop plants: cauliflower, papaya, chilli, tapioca in well-ordered rows. What is growing between the plants looks like shredded packing paper but is actually fibre remnants. The waste water from processing crop waste causes plants to grow. This could be called circular economy.

Published on KfW Stories: Wednesday, 16 January 2019

The described project contributes to the following United Nationsʼ Sustainable Development Goals

Goal 1: End poverty in all its forms everywhere

Around eleven per cent of the worldʼs population lives in extreme poverty. In 2015 that figure was around 836 million people. They had to live on less than USD 1.25 a day. The global community has set out to end extreme poverty completely by 2030.

All United Nations member states adopted the 2030 Agenda in 2015. At its heart is a list of 17 goals for sustainable development, known as the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs). Our world should become a place where people are able to live in peace with each other in ways that are ecologically compatible, socially just, and economically effective.

Data protection principles

If you click on one of the following icons, your data will be sent to the corresponding social network.

Privacy information