The Indian Silicon Valley is located in the state of Karnataka. Part of the electricity that is urgently needed in Bangalore, an Indian city with millions of inhabitants, is now supplied by a small village with its solar power plant. The use of renewable energies in India is indispensable. The country is already the third largest electricity consumer in the world.

Control

Near the village of Bevinahalli, 3,000 photovoltaic panels provide green electricity. The maintenance of the area has created new jobs.

Bevinahalli is located about 150 kilometres north of Bangalore. 5,000 people live in Bevinahalli and many of them keep sheep. Bangalore, capital of the state of Karnataka and India's third largest city, is home to 8.5 million people, many of whom work as programmers. The Silicon Valley of India is booming. It requires electricity – lots of it. It gets some of its supply from the farming village of Bevinahalli.

Just outside the village, 3,000 photovoltaic panels glisten in the sun. Surrounded by a concrete wall about two metres high, the solar power plant is divided into several plots and produces a total of 33 megawatts of electricity. KfW financed a 10-megawatt plant on the site with a loan via the Indian Renewable Energy Development Agency (IREDA) to the operator of the plant, Asian Fab Tec. The output corresponds to the electricity demand of 2,000 households. KfW has made several loans available to IREDA for sustainable energy generation, most recently EUR 100 million. This will allow the installation of 124 megawatts of capacity for electricity generation from wind and solar energy and save 286,000 tons of CO2 per year.

Bevinahalli's solar plant is built on stony ground. It is not particularly fertile, which makes it affordable. "Finding the land for a plant is one of the main problems," says Sudhir Moola, managing director of Premier Solar, the company that built the panels. A square metre in Bevinahalli costs around EUR 2.20, while good farmland would cost five times as much.

Supplier

The solar power plant produces a total of 33 megawatts of electricity. One of its clients is Bangalore, India's third largest city.

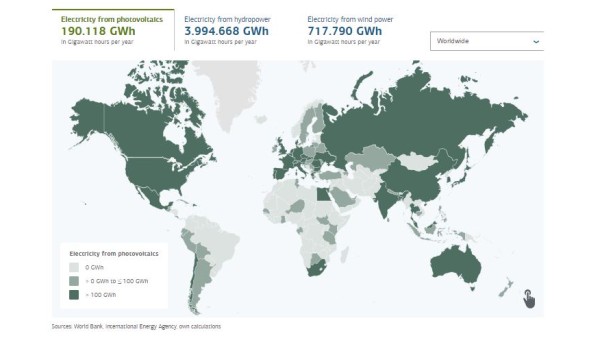

With its 1.3 billion people, India is the third largest electricity consumer in the world (after the USA and China), but also the third largest greenhouse gas emitter. And the forecasts for the future are dizzying: the country's electricity consumption is expected to double by 2027 and even multiply by six by 2047. The use of renewable energy sources is indispensable for reasons of climate protection alone. Renewables currently account for 20 percent of installed electricity generation capacity. This is expected to approximately double by 2030. Currently, however, most of India's electricity still comes from coal and gas-fired power plants.

The people of Bevinahalli were already connected to the power grid before the construction of the photovoltaic system, but the solar power plant has brought jobs for some of the villagers. For example, the plant requires cleaning personnel. The panels must be washed once a month. The water – one litre per panel, per month – comes from a well on the plant grounds.

The village also benefits from the photovoltaic system in other ways. The operating company, Asian Fab Tec, supplied cattle feed, built a school and secured the water supply. According to Carolin Gassner, head of the South Asia division at KfW, the commitment in Bevinahalli is thus exemplary for the purposes of KfW's loan financing in the energy sector, which include "reducing carbon dioxide emissions, combating poverty and promoting renewable energies". It is "cooperation on a level playing field to solve problems of not only a local but a global dimension," says Gassner.

In the countryside, poverty is still widespread and people are crowding into the cities. The urban population is currently growing at a rate of 2.4 per cent per year. It is expected that in 2030 about 600 million Indian people will live in cities. The wind turbines and solar parks, however, are located in rural areas, such as Bevinahalli, and in the southern Indian state of Karnataka, which with 12 gigawatts of installed capacity from renewable energy sources is the leader of all states in terms of green electricity.

Location factor

”Finding the land for a plant is one of the main problems,“ says Sudhir Moola, managing director of Premier Solar, the company that built the panels. A square metre in Bevinahalli costs around EUR 2.20, while good farmland would cost five times as much.

Distributor

The new switchgear substation is located near the city of Hindupur. The energy from around 4,000 wind turbines is converted here and fed into the power grid.

Long lines are needed to transport the green electricity to the industrial and population centres. For this purpose, the Indian government is building "green corridors". Expressed in figures, the project covers almost 8,000 kilometres of power lines, with 77 switchgear substations. However, since electricity from wind and sun cannot be generated constantly for 24 hours as in conventional power plants, the transmission lines fed with renewable energy are less utilised, which makes them less profitable and therefore requires low-cost loans. And that's where KfW comes in.

It has lent EUR 500 million to the national grid operator Power Grid Corporation of India. It counts as one of the largest credit transactions in KfW's history. A loan of the same amount is shared by the network operators of seven federal states. In the coming years, an additional EUR 400 million from KfW funds is to flow into projects in the green corridors. This represents a total investment of EUR 1.4 billion.

To make the flow of electricity efficient, switchgear substations must convert low-voltage energy from wind and solar power plants into high-voltage energy, which then finds its way into the population and factory centres. Near the city of Hindupur there is a brand new switchgear substation built by a Tata Group company and operated by Aptransco, the state grid operator. The station receives electricity "from 4,000 wind turbines within a radius of 120 kilometres", reports Tata manager Dileswar Sahoo. The switchgear substation is located in the state of Andhra Pradesh, not far from the border with Karnataka. In border regions within India, the electricity grids are traditionally less developed and more unstable, which is why the Green Corridors project is again of particular importance here.

KfW and the state each contribute 40 per cent to the financing of the Hindupur switchgear substation, with the remaining 20 per cent coming from the grid operator. Tata manager Sahoo estimates the incoming electricity at 1.2 gigawatts, which is roughly equivalent to the output of a German nuclear power plant.

Just an hour's drive from the Hindupur switchgear substation, the Korean car manufacturer Kia is building a plant. Beginning in spring 2019, up to 300,000 vehicles will roll off the production line here every year. This investment will put a total of 11,000 people in paid employment in the middle of the countryside. A stable, high-performance power grid is a key factor for locating industrial settlements, especially in an emerging economy like India. If the electricity comes from renewable energy sources, climate protection will also be taken into consideration in the promotion of economic development.

Published on KfW Stories on 28 November 2018, updated on 20 July 2022

The described project contributes to the following United Nationsʼ Sustainable Development Goals

Goal 7: Ensure access to affordable, reliable, sustainable and modern energy

Close to 80 per cent of the energy produced worldwide still comes from fossil fuel sources. Burning fossil fuels also generates costs for the health system due to air pollution and costs for climate-related damages that harm the general public, not just those burning the fuel.

All United Nations member states adopted the 2030 Agenda in 2015. At its heart is a list of 17 goals for sustainable development, known as the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs). Our world should become a place where people are able to live in peace with each other in ways that are ecologically compatible, socially just, and economically effective.

Data protection principles

If you click on one of the following icons, your data will be sent to the corresponding social network.

Privacy information