On the Indonesian island of Sumatra, Dr Peter Pratje from the Frankfurt Zoological Society (Zoologische Gesellschaft Frankfurt: ZGF) has been running the Bukit Tigapuluh landscape conservation programme for over 20 years. The project, which is based in one of the country's largest continuous lowland rainforests, focuses on resettling orangutans and conserving the living environment for the area's unique flora and fauna. KfW is supporting this work

How transformation succeds in Indonesia

(Source: KfW/ Christian Chua / Thomas Schuch)

Resocialisation

Alda spent 19 years as a pet in a cage. Now she could move freely through Bukit Tigapuluh, but she doesn't know how to do this any more.

Alda is 23 years old, pregnant, hungry and not really sure whether she is coming or going. The jungle of Bukit Tigapuluh is still foreign to her and life as a free orangutan is obviously not her thing. If she were human, you would probably say she was suffering from something like post-traumatic stress disorder.

Alda's life story is tragic: she was kept as a pet for 19 years, living in a small cage in a small town until the day her owner passed away. As the owner's son didn't have a clue what to do with Alda, he opened the cage door. She climbed out, left the house and climbed the nearest coconut tree, where she remained for four whole days until someone informed the wildlife authorities.

Alda was picked up and taken to the quarantine station in Medan in northern Sumatra. Alda has since been free for almost two years and now lives in Bukit Tigapuluh. She was the 162nd orangutan to be released into the rainforest as part of the Bukit Tigapuluh conservation programme.

Shelter

Many rare animals profit from the 145,000 hectare conservation area on the Indonesian island of Sumatra: tigers, elephants, tapirs - and for some years now also orangutans again.

Set up 16 years ago, the aim of the programme is to establish a sustainable population of Sumatran orangutans in Bukit Tigapuluh and thus help to protect the Pongo abelii species from extinction. The animals supported by the resettlement programme are either confiscated animals rescued from illegal captivity, like Alda, or orangutans who have lost their homes during the deforestation of Sumatra's forests. A select number of zoo animals are also among the new citizens in Bukit Tigapuluh. The programme's second major goal is to protect as much of the orangutan's natural habitat as possible.

The Sumatran orangutan is a species under threat. According to estimates, a mere 14,600 or so animals still live on the Indonesian island. One issue that makes their survival particularly tough is the loss of their natural habitat. Deforestation rates in Indonesia and especially on Sumatra are sky high; tropical forests are disappearing faster here than anywhere else on earth. Between 1985 and 2007 alone, around 12 million hectares of forest were cleared. This means that close to 50 per cent of Sumatra's total forest area has been destroyed in just 22 years.

Indonesia

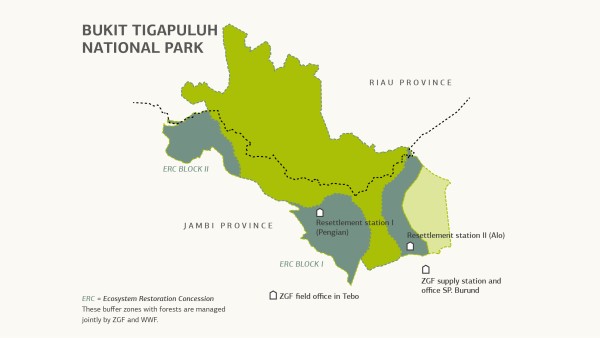

Location of the reserve in the middle of Sumatra's forests. The ZGF regional office is located in the provincial capital of Jambi, about 200 kilometres from the Bukit Tigapuluh National Park.

The felled trees are used to make paper. The majority of the cleared areas are then used to plant oil palms. Rows and rows of these trees stretch for hundreds of kilometres, so straight they could have been drawn with a ruler. Indonesia is the world's main producer of palm oil, which is used in an incredible number of products from food and cosmetics to biodiesel. For Sumatra's wildlife, whose survival depends on the rainforests staying intact, this development is putting their future at risk.

Bukit Tigapuluh National Park covers 145,000 hectares in the provinces of Jambi and Riau in central Sumatra. The park is now home to the island's last lowland rainforests, where tigers, elephants and tapirs have been rejoined by orangutans over the past few years. In late 2002, the recently completed resettlement station in Bukit Tigapuluh welcomed the first five rescued orangutans back into the ecosystem: Waikiki, Madu, Roma, Santi and Ricki. Their arrival was preceded by many years of preparatory work, extensive feasibility studies and an in-depth search for a suitable location for the resettlement station.

First training

The animals are prepared at the Open Orangutan Sanctuary release station near the Bukit Tigapuluh National Park. Here, for example, fruits are presented to them out of reach. They must use branches to fish for them.

Upon their arrival, the five resettlement candidates were greeted by state-of-the-art cage systems and the programme's director Dr Peter Pratje and his team. While the team had all received outstanding theoretical training and preparation, they were not entirely sure what would happen next when it came to the practical side. "For the first two years, we learned more from the orangutans than they did from us," remembers Peter Pratje. "They showed us the best way to complete the resettlement process, which fruit they liked the best and the most effective way to train them."

Slowly but surely, they eventually created a training plan for the jungle school. Nowadays, this plan is used to prepare rescued orangutans for their new life in the wild. The great apes learn how to climb, build a nest to sleep in, what to eat and the best way to suck termites out of their nests. In short, they learn everything an independent ape needs to live freely in the rainforest. The programme has since become the first scientifically documented resettlement programme for orangutans and, as the data has demonstrated, the most successful of its type.

Last bastions

This is what the jungle of Sumatra once looked like. Today there are only forest islands left.

In addition to species protection, Peter Pratje and his team are now focusing their efforts on habitat conservation in Bukit Tigapuluh. This is because the forest is continuing to shrink at an alarming rate. In order to protect the few natural forests outside the national park that remain intact and save them from deforestation, ZGF and WWF have been working together for a number of years to obtain the concession rights to manage two blocks of forest neighbouring Bukit Tigapuluh National Park.

When the Indonesian Ministry of Forestry finally issued the licence on 24 July 2015, it marked the end of a five-year uphill battle against the district government. The perseverance of ZGF, WWF and the other project partners was rewarded with a conservation concession for 39,000 hectares. The licence, known as an ecosystem restoration concession, is in place for 95 years and is managed by a non-profit company set up especially for the project.

Everyday life in the jungle school

Branches instead of cage bars

Some monkey mothers in the release station do not know what to teach their babies after decades of captivity. To make sure that the monkey children don't even get used to life in a cage, they go to the jungle school. There they learn from their coaches and fellows how to survive in freedom.

As part of the International Climate Initiative (IKI), the German Federal Ministry for the Environment has provided funds via KfW to be used for the management of the concession zone. "The project is important to us, not just because it helps to protect the ecosystem and thus the habitat of endangered species like the orangutan in Bukit Tigapuluh National Park. It is also important because it simultaneously enables concepts to be developed that will improve the financial sustainability of long-term conservation," says Carsten Kilian, the responsible project manager at KfW Development Bank.

Last warning

Sumatra elephants are prevented from destroying fields bordering on the conservation area by ear-deafening ricochet cannons. This prevents conflicts between farmers and animals.

The ecosystem restoration concession is a major coup for Peter Pratje and all the organisations involved, though in reality it is just one of many milestones. "We are keen to establish long-term prospects for conservation and develop a participative forest usage plan, which gets local people involved in the sustainable and environmentally friendly use of the forests," says Peter Pratje.

In addition to providing a new home for orangutans, the concession zone is also an important habitat for Sumatran tigers and Sumatran elephants, both of which are classed as highly endangered. The Bukit Tigapuluh conservation programme is helping to ensure the survival of these species, too.

The Sumatran elephant conservation project has been fitting Sumatran elephants with radio collars since 2012 so that it can collect key data about elephants' behaviour. These collars also allow the project team to track the animals — even through the dense rainforest — and warn villagers if elephants are heading in their direction. This is thus an effective way to prevent conflicts between the hungry elephants on the one hand, and the farmers trying to protect their fields, on the other.

Localisation

Wild animals are equipped with transmitters. The Sumatran Orangutan Rescue Centre team can thus track them in the dense rainforest with telemetric equipment.

"When I started the orangutan resettlement project, I would never have believed that the job spec for my work would change so drastically," admits Peter Pratje. "What started out as a project to protect a particular species has since turned into an ambitious landscape conservation programme and everything that this entails."

Like in all other ZGF project areas, ecological monitoring also takes place in Bukit Tigapuluh and the conservation concession zone. The project's 58 camera traps have already captured evidence of over 30 species of mammals living in the ecosystem.

The team designs environmental education programmes for children and young people living around the national park. Recently, the first ever agricultural college for young people was opened at the edge of the park, enabling students to learn modern, profitable and sustainable methods of farming that can be applied to even small areas of land. Highly trained ranger units patrol the national park and work with the authorities to tackle illegal activity. All measures are designed to use natural resources as sustainably as possible and thus retain as much of the living environment as is feasible.

Field work

A team from the Wildlife Protection Unit collects data on a field near the conservation zone. The employees move on motocross bikes through the impassable terrain.

A long time has now passed since the project began in 2002; the orangutan population in Bukit Tigapuluh is growing and now it's no longer down to just resettled animals. Babies are now appearing in the population on a regular basis. The first jungle baby was born back in 2004. Santi, who was among the first intake of jungle students just two years earlier, gave birth to her daughter Suci in the forest.

Vanilla became the last baby to be born in the wild almost 18 months ago. She and her mother Violett appear at the resettlement station every few months or so. Now Alda has welcomed her baby into the world, too. Born in early 2018, it can enjoy freedom in Bukit Tigapuluh National Park in Sumatra.

Published on KfW Stories on 8 March 2018, updated on 4 November 2023.

The described project contributes to the following United Nationsʼ Sustainable Development Goals

Goal 15: Sustainably manage forests, combat desertification, halt and reverse land degradation, halt biodiversity loss

Biodiversity loss is increasing, and with it, the basis of our lives is being rapidly destroyed. According to estimates, 60 per cent of the worldʼs ecosystems have declined or are not used sustainably. 75 per cent of genetic diversity in agricultural crops has been lost since 1990. More than half of the rain forests have been destroyed in favour of producing palm oil, biofuels, animal feed and meat.

All United Nations member states adopted the 2030 Agenda in 2015. At its heart is a list of 17 goals for sustainable development, known as the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs). Our world should become a place where people are able to live in peace with each other in ways that are ecologically compatible, socially just, and economically effective.

Data protection principles

If you click on one of the following icons, your data will be sent to the corresponding social network.

Privacy information