Even systemically relevant retailers like bakeries have suffered during the coronavirus crisis – which means their suppliers have, too. Wachtel, the German market leader for bakery ovens and cooling systems for artisan bakers, therefore applied for financial aid at short notice. However, they have only drawn down a small portion of it.

Managing director Oliver Frey is passionate about high-quality bakery ovens.

Oliver Frey gets emotional when he talks about bakery ovens. When the subject turns to the cheap crisping ovens with air circulation that are now found in many discount supermarkets, he sounds angry: “They heat up and dry out cheap produce; they have nothing to do with real bakery ovens with top and bottom heat.” When talk turns to real bakery ovens, he becomes enthusiastic. They are his passion after all. Frey is the owner and managing director of Wachtel GmbH from Hilden in North Rhine-Westphalia (Germany), a family-run SME now in its third generation. According to the company, its products are the "Porsche" in the world of bakery ovens for artisan bakers: premium branded products, Made in Germany. Founded on Corneliusstrasse in Düsseldorf in 1923, the business moved to the suburb of Hilden in 1970 following strong growth. Oliver Frey has been in charge of the company since 2013 after buying it from his father-in-law. Based on its most recent figures, Wachtel’s products generated an annual turnover of around 40 million euros.

Wachtel is an established name in bakeries in Germany and around the world, and is beloved by bakers. And yet, its test bakery recently stood empty. Due to the coronavirus rules, no potential customers were able to use the showroom to find their ideal product. The test bakery is normally heavily frequented by both domestic and international customers, who work with the in-house master bakers and technology to define a suitable oven. The ovens are often two metres tall, weigh over a tonne and are equipped with several different levels for produce. Every detail is carefully thought out, just like at Porsche, for example. But what makes the ovens different to a car? Wachtel takes more of a custom-made approach to manufacturing. There are no traditional warehouse goods used to screw together the same machines over and over again. Every product is manufactured in line with the customer’s requirements at one of the two German production sites – in either Hilden, close to Düsseldorf, or Pulsnitz near Dresden.

Read more under the gallery.

Founded in 1923, the Wachtel company has been a family business for three generations now. This model stems from the times of the German ”economic miracle“.

Decisions over new high-tech ovens were postponed

When the coronavirus pandemic started to spread through Germany, bakeries were classed as ‘systemically relevant’ because people always need bread. And yet, Wachtel was still hit hard by the coronavirus crisis. Incoming orders dropped so sharply in March and April that Oliver Frey sought external support.That’s because, even though bakers were still allowed to open due to their systemic relevance, they were keeping hold of their money. “Income from deliveries to schools, catering facilities and their adjoining cafes disappeared, which hit a lot of bakers hard,” explains Oliver Frey. “And, of course, there was no passing trade in many town and city centres as people had stopped shopping and going to work.” As such, he explains that many bakers thought twice about whether now was the right time to buy a new oven. While no-one in this profession would be able to do without a professional high-tech oven for the long term, explains the Wachtel boss, “they can still put off ordering one for a few months if pushed.”

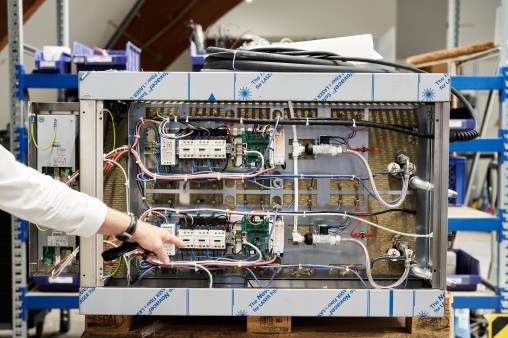

The costs for an oven vary between 20,000 and 100,000 euros – depending on what the customer needs. That is a lot of money, even though investing in an oven like this is not a frequent occurrence. “If they are well maintained, our bread ovens last 30 to 40 years,” says Frey. Emphasis is on the word “maintenance” here. Wachtel look after this aspect, too. Because the main factory in Hilden and the second production plant in the state of Saxony produce almost all of the components for the ovens themselves, Wachtel service technicians are able to solve practically any problem with the equipment without any external support. From the wiring and heating elements to the high-tech control displays on the most cutting-edge product lines, everything is screwed together in the huge hall next to the company’s headquarters.

“The Americans have Silicon Valley, we have the craft of bread-making.”

It takes four to eight weeks to produce a premium oven depending on the customer’s requirements. As well as bakeries, Wachtel also supplies hotels, like the Adlon in Berlin, and ships, including the Aida fleet. The company added cooling technology to its portfolio in 2005. Frey explains that good cooling equipment is just as important for bakeries as a good oven. “In addition to having the right recipes, it is also the cold air that creates the flavour of the bread’s dough due to enzymology,” he explains. Wachtel delivers almost 50 per cent of its ovens across the globe. The markets in Eastern Europe and Asia are particularly attractive, says Frey. “The people there are just as fond of their bread as the Germans are and their spending power is growing all the time. It is now worthwhile for local bakers in these markets to choose our ovens over those from our cheaper competitors,” he says. He goes on to explain that Made in Germany is still a quality label – and the country’s reputation when it comes to the bakery sector is even better. “The Americans have Silicon Valley, we have the craft of bread-making; we are the bread world champions,” explains Frey. The mere fact that Germany is the only country where ‘baker’ is a recognised profession requiring official training demonstrates the high status awarded to this profession.

Business began to recover as early as May

However, internationalisation and a good reputation cannot help in the era of coronavirus. Barely any new orders arrived in Hilden in the first two months of the crisis. So, Oliver Frey turned to the company’s regular bank, Sparkasse Hilden-Ratingen-Velbert. Christoph Smolka is the bank’s director of corporate clients. He did not have to think twice about providing assistance to this long-established and profitable SME. “Wachtel has been our client for decades so we know the business well,” he says. The company is built on a sustainable structure and has a successful business model. As a result, Wachtel also qualified for a KfW Entrepreneur Loan. This was provided by Sparkasse in conjunction with Postbank and Commerzbank. In total, the coronavirus aid amounting to 2.4 million euros was enough to secure liquidity for a few months.

“We have only drawn down half of the loan,” says Oliver Frey. Things suddenly began to look better again when the easing measures were introduced. “We started to get back on track again in May; our incoming orders were even 20 per cent higher than the same month last year.” It seems that German bakers also believe that investments are once again worthwhile.“KfW’s coronavirus aid was developed precisely to bridge liquidity shortages like this,” says Markus Merzbach, Director at KfW. “So, of course, it is even more pleasing to hear that the situation is starting to improve sooner than anticipated. Though, naturally, this differs from sector to sector.”

There were no coronavirus-related job losses at Wachtel because the order books were already full before the crisis. “We had to deal with all those orders first, so we still needed all our staff. This was our top priority, too,” says managing director Frey. Even in February – before the pandemic had reached Germany but was already causing difficulties in Asia – the company began to introduce precautions to protect its employees. For instance, a two-shift system was introduced for separate teams in production to guarantee the necessary distance between staff. “Thanks to these forward-looking measures, we did not have to push back a single delivery deadline in Germany,” reports Frey. The company was working at around 75 per cent capacity in the months of April and May. In view of the upturn in orders, both German plants will be back at full capacity in June and July.

Published on KfW Stories: 30 June 2020.

Data protection principles

If you click on one of the following icons, your data will be sent to the corresponding social network.

Privacy information