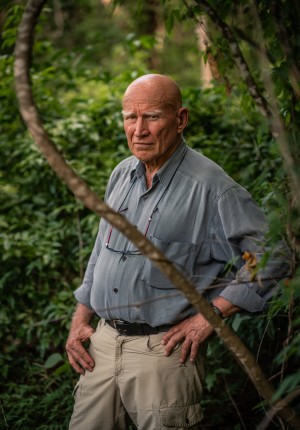

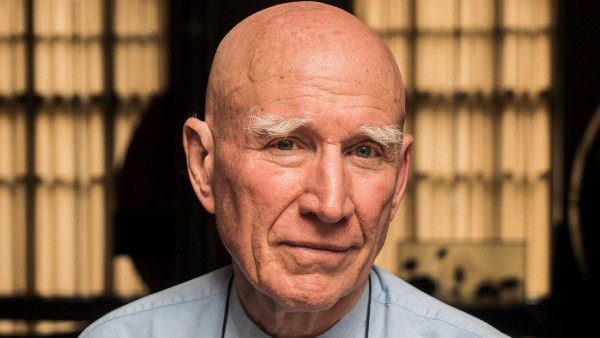

For over two decades, the Brazilian star photographer Sebastião Salgado (1944-2025) and his wife Lélia have been reforesting the region of his birth. The two also had KfW at their side for their ambitious project. In 2021, KfW Stories met the couple exclusively on the premises of the organisation he founded, Instituto Terra.

Interview with Sebastião Salgado from the year 2018

Source: KfW / Thomas Schuch

As evening descends, so does the urgently anticipated rain. The wind drives the water forwards at a slanted angle, with thick raindrops beating down onto the dried-out ground and trees shaking with every gust. In the glow of the sheet lightning, the tropical thunderstorm feels like a silver curtain that has pulled itself in front of the panorama of palm trees, shrubs and flat houses.

The rain pelts the roofs with such force that those inside have to raise their voices in order to be heard. While the brownish floods dart from the slopes onto the pathways and into the water lily pond, a phone tree informs all the men to be present and correct first thing in the morning, even though the weekend has just begun. They now have a good chance to make up for lost time.

Even before the clock strikes seven in the morning, there is a group gathering on a small veranda belonging to the Instituto Terra. The sun is there, peeking through the heavy, dark clouds once more. Clad in khaki uniforms, those assembled sit on a low wall or stand in a semi-circle around Sebastião Salgado. In his other life, Salgado may be one of the most renowned photographers in the world, having been decorated with dozens of prizes, including the Friedenspreis des Deutschen Buchhandels, a peace prize awarded by the German book industry. He is here in his role as the founder of Instituto Terra. Along with his wife, Lélia, he is the initiating force and fount of ideas behind this reforestation project on the family’s old ranch in the small Brazilian town of Aimorés, ten hours’ drive up the coast from Rio. And so on this morning, shortly after the passage of the New Year, he prepared the men for the days to come. “We haven’t got much done since October. Only 5,800 saplings have been planted so far,” he says. “We have to take advantage of last night’s rainfall and get as many young trees out there as we can.”

Rainforest has been created metre by metre

About Mr Salgado

When Sebastião was born on his family’s farm in 1944, the land was still fertile. As a boy, Sebastião accompanied his father and the farm workers when they drove a herd of animals to the nearest abattoir every 50 days. It was at that time that he formed a deep connection with the Rio Doce Valley in the state of Minas Gerais. But as an economics student in São Paulo, he and his wife Lélia had to flee the military dictatorship for Paris in 1969. It was there that he began his career as a photographer. When he returned to Brazil, tired and unwell after years of photographing war and disasters, violence and genocide, his wife came up with the idea of reforesting the family’s old ranch. And Salgado found the strength to take photos once again. This time, capturing the beauty of remote areas of Planet Earth. He titled the project, which followed his trademark black and white style, Genesis.

Specifically, that means having to put more than 16,000 extra saplings into the ground within an extremely short period, provided that the soil retains its moisture. At various points on the mountainous terrain, at a distance of three metres. Immediately after the speech is over, the men pull thick gaiters over their boots to protect them from venomous snakes, carrying their water canisters and boxes of food under their arms. Shortly afterwards, they disappear into the thicket, where a metre-deep, machine-milled hole takes one sapling at a time. A worker previously spreads natural fertiliser into the loosened soil. Then another plants a young tree – perhaps 20, perhaps 40 centimetres tall – in the hole.

Within 20 years, this has made it possible to create a tropical rainforest on 600 hectares of once barren terrain including washed-out slopes – one planting process after another, one metre after another. Some 2.7 million trees have plugged one of the holes in the Mata Atlântica, the Atlantic Forest that was heavily deforested in the 20th century in the mountainous coastal region of southern and eastern Brazil. There are now 293 different plant species growing in this area, including grasses, mosses, flowers, shrubs and trees. Many of the plants do not exist anywhere else in the world.

The trees cut a particularly impressive figure. Looming large among them are the knotty, oak-like cerejeira; the slender, smooth cascudeira with its protruding crown; the chestnut-like sapucaia; the branchy candeia; and the peroba, slowly but sweepingly soaring skywards. The latter has almost disappeared, as its reddish-brown tropical timber is so durable and attractive that many people able to afford it have used the wood to deck out their floors, doors and windows at home.

In some instances, the trees’ bark is smooth; in others, it is furrowed. In some instances, they have fast-growing trunks, whose branches only spread to their widest extent in their upper reaches. In others, their trunks and limbs branch out not far above the ground, twisting and turning towards the sky at various angles. And under, on and between them, the animal world has also developed, with 172 different species of bird alone living in these arboreal realms. Insects, reptiles, rodents and mammals have also found a new home here. Even the now rare maned wolf has returned, along with its family. As has a puma, padding through the young forest. This has made the project a flagship effort, unparalleled anywhere else in the world.

From a slope at the edge of the now 700-hectare ranch, the Salgados savour a view over the part of the Mata Atlântica that they have reforested.

The idea behind it came from Lélia Salgado. At first, the whole thing seemed more like help for a soul in torment than for an environment in distress. Lélia’s husband Sebastião had become so ill that he was thinking of putting down his trusty camera for good, having spent years documenting hunger and poverty, war and violence – a photographic repository of the depths to which the human race can sink. Upon returning from the Congo and Rwanda in the mid-1990s, where he had captured images of the genocide against the Tutsi, he was more than just miserable. His urine had turned blood-red and he was sure that he was suffering from cancer. After thorough examinations, his doctor in Paris told him that his body was healthy, but his mind was ailing.

Instituto Terra launches reforestation programme

The green thicket is their doing! Over the last 20 years, Sebastião and Lélia Salgado have invested two to three million dollars of their own money to develop the Instituto Terra. They don’t know the exact figure.

So the Salgado duo took some time off in their native country of Brazil. They had left as students in 1969, fleeing from the military dictatorship and its henchmen, who had imprisoned and tortured fellow students at the University of São Paulo. Only towards the end of the regime were they able to return to Brazil, after more than ten years. The refugees had since become French citizens. And even though they now regularly headed back to their old home, their primary residence was still in Paris. During that period of rest and recuperation by the South Atlantic, Salgado’s father decided to hand his farm over to the kids: his seven daughters and his son Sebastião. The land once included pasture for up to 10,000 cattle to graze, was home to countless pigs, and provided a source of food for 30 families from its livestock, rice and sugar cane operations. But as time had passed, the ranch had dried up much like the entire region. Where four animals could previously find enough food on a single hectare, each cow now needed more than one hectare of pastureland. In addition, a fast-growing grass imported from Africa had displaced the native species, the water table had fallen, and annual rainfall had halved over time from 1,200 to 600 millimetres per square metre.

It was during this time in the late 1990s that the idea for the Instituto Terra and the regional reforestation programme arose. The transformation of this tormented strip of land into a tropical paradise was also intended to cure Sebastião Salgado, allowing him to soon get underway with his major photographic project, Genesis. This would examine the beauty of some of the most untouched corners of Planet Earth.

Initial setbacks and new reforestation methods

The people in this area of Minas Gerais state were initially sceptical about whether such a project could succeed. Whether the famous, globetrotting photographer had not only lost touch with his homeland, but had also had his head filled with the sort of ideas commonly held by city-dwellers and Europeans. Even Salgado’s father, who had started to build up the largest ranch in the area in the 1930s, had doubts about his son and daughter-in-law’s ideas.

Many of the trees planted have since become so large that they not only provide shade for more sensitive plants – birds and mammals have also come back, with even a native wolf species and a puma returning to the area.

And in fact, the first years after the Instituto Terra was founded were difficult. It was not a case of constantly raising enough money from financial backers to start developing the fallow land and create a tree nursery. Initially, up to 50 per cent of the trees planted were lost, with the saplings going into the ground either too early or too late because the rain failed to arrive. “We first had to learn the lesson that young trees don’t stand much of a chance unless we subject them to some stress and strain before planting. They also have to get used to dry spells,” Sebastião Salgado says, thinking back to this period.

In the meantime, the workers in the institute’s nursery reduced the amount of water per day, as well as the number of days they water the plants, before taking them out of the seed tray and into the wild. This means the young trees become strong enough to take root and survive even through years with little rainfall. Today, nine in ten saplings survive the critical first years. These are mostly planted between December and April.

KfW supports the project

In view of these successes, KfW was also prepared to support the project over the next four years with 13.1 million euros in German Federal Government funds. “Salgado may have become famous for his black and white photos,” says Karim ould Chih, who supervises the programme for KfW Development Bank, “but in this case, he and Lélia are bringing colour back to nature.”

Those in charge in Aimorés want to use the money from Germany to expand their work outside the farm itself. The aim is for thousands of farmers in Rio Doce Valley to create small forests on their land in the coming decades. The Instituto Terra’s technicians began helping farmers with this a number of years ago. By reforesting one hectare of land at a time, the existing water sources can be protected and strengthened. Nine hundred trees and a barbed wire fence are needed to make this happen, an investment of around USD 3,000. The fence does more than simply prevent larger animals from eating away at the young trees. The 500-kilo cows’ hooves are even worse for the soil.

João Honoratio Mugia is one of these farmers. Mugia, 55, began planting trees on the hillside above his house almost nine years ago with the help of the Instituto Terra. Just two years later, he could see that the local spring held more water than before, enough to supply not just the family household, but also to irrigate 1,000 coffee plants – and, in turn, increase his income.

Mugia climbs up the slope in flip-flops to point out the source of the spring and its protective fence. This also protects a number of trees, which have since grown magnificently. “At first, I didn’t know whether it would be worth it,” he says in the shadow of his plantation. “I regularly had to rent others' land so I could feed the few animals I had. This is why I decided to plant trees on about one of 25 hectares of land I own. Today, I’m glad I did it.” A thousand farmers have followed in his footsteps in recent years. Another 5,000 are still to come with KfW’s support. In the long term, the idea is for 50,000 landowners in the Rio Doce Valley – covering an area almost as large as Portugal – to join the programme. This would create a chain of small forests, which would absorb large amounts of carbon dioxide as well as sustainably improving the region’s microclimate.

The clock is ticking. Experts fear that the climate could change faster than the trees are able to grow, jeopardising the prospects for reforestation as the area becomes drier and drier. But even if these experts are right, the people here have no alternative. “From the very beginning, we felt it was important not to act without those who live here, or to go against their wishes,” Sebastião Salgado explains. “As important as discussions and conferences on climate change are, many forget that they need to involve those affected. Otherwise, it’s all just talk.”

So far, the Salgados have ploughed two to three million dollars of their own money into the project. They don’t know the exact figure. It costs 600,000 dollars per year just to cover the costs of maintaining the buildings and paths, paying the salaries of the 50 to 60 employees, and supporting the 20 students. Each of these students is given accommodation and taught here free of charge for a year, enabling them to train as technicians and master the arts of growing and planting.

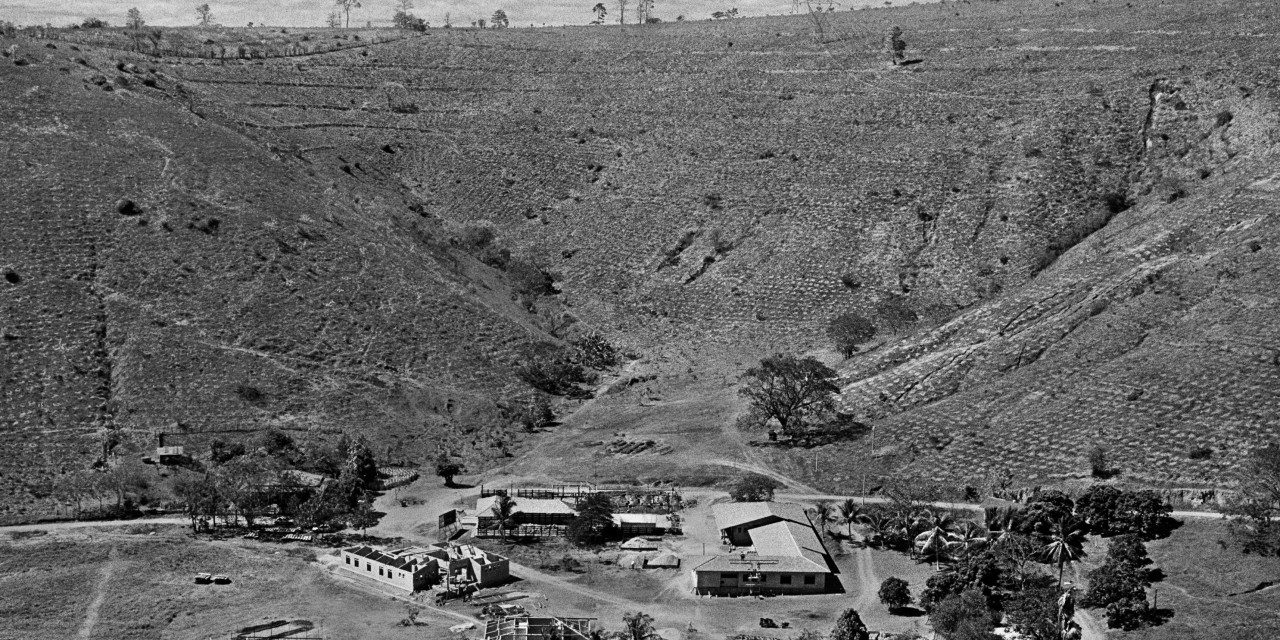

Before – after

The land owned by Sebastião Salgado’s environmental protection organisation Instituto Terra before and after reforestation. Use the mouse pointer and drag the arrow to the left to see how it has changed.

The Salgados plan successor for the Instituto Terra

As a result, the Salgados are always on the lookout for donors, whether in the form of companies, business owners, celebrities or wealthy private individuals. Some years before his death in 2014, the actor Robin Williams had financed the Instituto’s auditorium, including its stage and film projection equipment. Prince Albert II of Monaco has always been willing to lend a helping hand through his foundation. There are also donations from large companies; not only from Brazil, but also from distant countries like Switzerland.

Sebastião and Lélia Salgado have since retired from their daily work, with Lélia handing the Instituto’s director post over to a younger woman some time ago. And since he is now 77 years old and she is only three years his junior, the two are mainly concerned with the question of how things can go on after them. The Salgados remain active on the Instituto’s board of directors and come to Aimorés several times a year to ensure they stay up to date. This year, they will also seek to raise ten million dollars. They hope to use the money to establish a foundation and that the interest on these funds will cover future running costs.

“I’m confident that we’ll succeed,” says Sebastião, who is also planning various appearances in Germany to find major donors. “More and more people are realising how important this type of long-term work is.”

Salgado may be the most successful and famous photographer in the world right now. Millions visit his exhibitions, and thousands buy his books. The only thing on his mind? “The most important project of my life is the Instituto Terra.”

On 23 May 2025, Sebastião Salgado died at the age of 81 in his adopted home of Paris as a result of leukaemia, presumably caused by malaria, which he contracted in 2010 while recording for his ‘Genesis’ project.

Published on KfW Stories on 27 October 2021, updated on 26 Mai 2025..

The described project contributes to the following United Nationsʼ Sustainable Development Goals

Goal 3: Ensure healthy lives and promote well-being for all at all ages

Health is the goal, prerequisite and result of sustainable development. Supporting health is a humanitarian requirement – both in developed and developing countries. Around 39 per cent of the worldʼs population lives without health insurance. In poor countries, this amount even exceeds 90 per cent. Many people still die from diseases that are not necessarily fatal with the right treatment, or that could easily be prevented with vaccinations. Strengthening health systems, particularly by making vaccines widely available, can make it possible for us to drive these diseases back and even eradicate them by 2030.

All United Nations member states adopted the 2030 Agenda in 2015. At its heart is a list of 17 goals for sustainable development, known as the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs). Our world should become a place where people are able to live in peace with each other in ways that are ecologically compatible, socially just, and economically effective.

![[anwesen_salgado_wiederaufforstung:MEDIASTORE_LEAF]@e22b3be](kfw/bilder/umwelt/naturschutz/waldschutz-brasilien/anwesen-salgado-wiederaufforstung_rs_compare_module.jpg)

Data protection principles

If you click on one of the following icons, your data will be sent to the corresponding social network.

Privacy information